Understanding Pubic Lice

What are Pubic Lice?

Morphology and Life Cycle

Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis) are small, crab‑shaped ectoparasites measuring 1–2 mm in length. The body consists of a compact thorax bearing three pairs of legs, each ending in sharp claws adapted for grasping coarse hair. The head bears simple compound eyes and antennae with five segments. Males are slightly larger than females and possess a more robust abdomen; females exhibit a pointed posterior segment for egg deposition. The exoskeleton is sclerotized, providing protection against mechanical damage and desiccation.

Reproductive output follows a rapid, obligate life cycle:

- Egg (nit): Oval, 0.3 mm, firmly glued to hair shaft near the base; incubation lasts 6–10 days.

- Nymphal stages: Three molts occur at intervals of 3–5 days; each instar resembles the adult but lacks fully developed genitalia.

- Adult: Emerges after the final molt, capable of mating within 24 hours; lifespan ranges from 30 to 40 days under optimal conditions.

Females lay 1–2 eggs per day, depositing them near the hair follicle. Fertilized eggs hatch into mobile nymphs that immediately begin feeding on host blood, accelerating development. The entire cycle, from egg to reproductive adult, can be completed in approximately 2 weeks, enabling swift population expansion on a new host. Transmission primarily occurs through direct contact with infested hair, explaining the origin of infestations in human populations.

Common Misconceptions

Pubic lice are often misunderstood. Several false beliefs persist, each lacking scientific support.

- Poor hygiene as a cause – Cleanliness does not prevent infestation; lice feed on blood, not skin debris.

- Public swimming pools or hot tubs – Water does not provide a viable environment for lice survival; transmission requires direct hair-to-hair contact.

- Pets or other animals – Human pubic lice (Pthirus pubis) are species‑specific and cannot be acquired from dogs, cats, or rodents.

- Bed bugs or other insects – Bed bugs bite skin but do not transmit pubic lice; the two parasites are unrelated.

- Transmission through clothing or towels – Lice detach quickly from the host; indirect contact rarely spreads them, and standard laundering eliminates any risk.

- Exclusive link to sexual activity – While sexual contact is the most common route, close non‑sexual contact (e.g., sharing a heavily infested pillow) can also transmit lice.

Understanding these misconceptions clarifies that pubic lice spread primarily through prolonged head‑to‑head or body‑to‑body contact, not through hygiene practices, environmental exposure, or animal vectors. Accurate knowledge guides effective prevention and treatment.

Origins and Transmission

How Pubic Lice are Acquired

Sexual Contact

Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis) are small, wingless insects that inhabit the pubic region and other coarse body hair. They survive by feeding on blood and lay eggs (nits) attached to hair shafts.

Sexual intercourse is the principal pathway for acquiring these parasites. Direct skin-to-skin contact allows adult lice or nits to move from one partner to another. The transfer occurs during any activity that brings the pubic area into close contact, including vaginal, anal, or oral sex.

Common circumstances that increase the likelihood of transmission through sexual contact:

- Unprotected intercourse with an infected partner.

- Multiple recent sexual partners.

- Engaging in sexual activities with individuals whose infestation status is unknown.

Although occasional spread can happen via contaminated bedding, towels, or clothing, the overwhelming majority of cases originate from intimate contact. Prompt detection and treatment of both partners reduce the risk of reinfestation.

Non-Sexual Transmission (Rare)

Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis) are primarily spread through sexual contact, but transmission without sexual activity does occur, albeit infrequently. Non‑sexual spread requires direct skin‑to‑skin contact or the transfer of live insects from contaminated items (fomites) to a new host.

Documented non‑sexual pathways include:

- Sharing of clothing, underwear, or socks that have recently contacted an infested area.

- Use of shared bedding, towels, or linens that have not been laundered at high temperatures.

- Close, prolonged contact between family members, such as a parent handling an infant’s genital region.

- Contact with upholstered furniture, upholstered seats, or other fabric surfaces that have harbored lice or their eggs.

Epidemiological studies estimate that less than 5 % of pubic‑lice infestations arise from these routes. The insects survive only a few days off the human body, limiting the risk associated with contaminated objects. Prompt laundering of fabrics at temperatures above 50 °C (122 °F) or dry‑cleaning effectively eliminates viable lice and nits.

Recognition of non‑sexual acquisition is essential for accurate diagnosis and for advising patients on hygiene measures that reduce the likelihood of re‑infestation from shared items.

Risk Factors for Infestation

Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis) spread primarily through direct contact with contaminated hair or skin. Several conditions increase the likelihood of acquiring an infestation.

- Sexual activity with an infected partner, including vaginal, anal, or oral contact.

- Sharing personal items such as towels, bedding, clothing, or bathing accessories that have contacted an infested area.

- Close, prolonged skin‑to‑skin contact in non‑sexual contexts (e.g., co‑sleeping, communal bathing).

- Living in crowded environments where hygiene standards are low, such as shelters or dormitories.

- Lack of regular personal hygiene practices, including infrequent washing of genital hair.

- Immunocompromised status or skin conditions that compromise the barrier function, facilitating lice attachment.

Understanding these risk factors helps target preventive measures and reduce transmission rates.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Recognizing an Infestation

Common Symptoms

Pubic lice infestation presents with a distinct set of clinical signs. The most frequent manifestation is intense itching in the genital region, often worsening at night. Visible insects or their translucent eggs (nits) may be seen attached to coarse hair on the pubic area, as well as on the abdomen, thighs, or chest. Small, painless red or blue‑gray macules can appear where lice bite the skin, sometimes forming a linear pattern. Secondary bacterial infection may develop if scratching breaks the epidermis, leading to localized swelling, pus, or crusted lesions. In some cases, patients report a feeling of movement or crawling sensations within the hair shafts. These symptoms together provide a reliable basis for diagnosis.

Less Common Symptoms

Pubic lice infestations are typically identified by itching and visible nits, but several atypical manifestations may appear in a minority of cases.

- Secondary bacterial infection of excoriated skin, presenting as erythema, swelling, or pus formation.

- Persistent, localized dermatitis that does not respond to standard antipruritic treatments.

- Painful or inflamed lesions on the neck, chest, or abdomen when lice are transferred through contact with contaminated clothing or bedding.

- Unusual discoloration of hair shafts, ranging from yellow‑brown to gray, caused by prolonged feeding and debris accumulation.

- Systemic signs such as low‑grade fever or malaise, generally linked to extensive scratching and secondary infection.

These manifestations are less frequent than the classic pruritus but warrant clinical attention because they can complicate diagnosis and delay appropriate therapy. Prompt identification and treatment reduce the risk of escalation to more severe dermatologic or infectious complications.

Medical Diagnosis

Visual Inspection

Visual inspection is the primary clinical tool for identifying the source of a pubic‑lice infestation. The adult insect measures 1–2 mm, has a crab‑like shape, and clings to coarse hair in the genital region, perianal area, armpits, chest, and facial hair. Direct observation of live lice confirms active transmission, while detection of attached eggs (nits) indicates recent acquisition.

Key visual cues that point to the probable route of acquisition include:

- Presence of lice on multiple body sites suggests intimate skin‑to‑skin contact rather than indirect transmission.

- Clustering of nits near the base of hair shafts indicates recent infestation, often associated with recent sexual activity.

- Absence of lice on personal objects (clothing, bedding) reduces the likelihood of fomites as the primary source.

- Visible lesions or excoriations accompanying lice suggest vigorous scratching, common after sexual exposure.

When a practitioner conducts a systematic examination, the process involves:

- Inspecting the pubic hair with a magnifying lens or dermatoscope.

- Separating hair strands to reveal nits attached at a 45° angle to the shaft.

- Scanning adjacent hair‑bearing regions for secondary colonization.

- Documenting the density and distribution of insects to infer the most recent contact event.

By correlating the observed pattern of infestation with the patient’s recent history of close physical contact, visual inspection can reliably differentiate between sexual transmission, non‑sexual close contact, and rare cases of indirect spread through contaminated items.

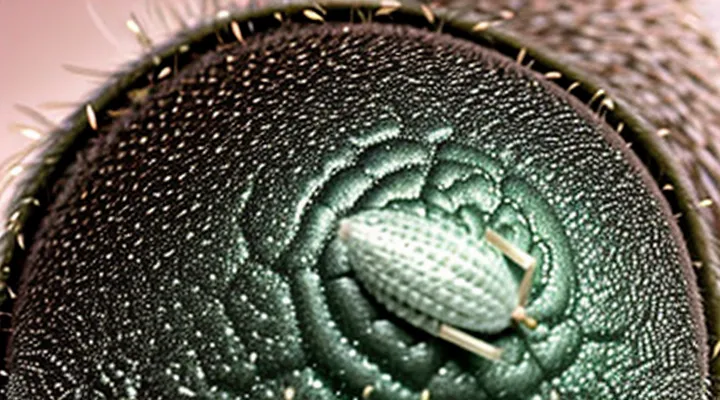

Microscopic Examination

Microscopic examination provides direct evidence of the biological source of Pediculus pubis. By preparing a slide of a collected specimen and applying high‑magnification optics, technicians can observe characteristic morphological features—such as the crab‑shaped thorax, enlarged posterior legs, and specific setae patterns—that distinguish pubic lice from head or body lice. These traits confirm that the infestation originated from the human genital region rather than from other animal hosts.

The procedure also reveals the presence of nits attached to hair shafts. Detecting nits confirms recent acquisition, because nits remain viable for only a few days after being laid. When nits are found on clothing, bedding, or personal items, microscopic analysis can differentiate human lice eggs from those of other insects, eliminating false assumptions about cross‑species transmission.

Key diagnostic steps include:

- Collecting live insects or nits with fine forceps.

- Placing specimens in a drop of saline or mounting medium.

- Covering with a cover slip and examining at 100–400 × magnification.

- Documenting morphological markers and measuring body dimensions.

- Comparing findings with reference images in entomological databases.

Through these observations, clinicians can trace the infestation to direct human‑to‑human contact, confirming that pubic lice are not acquired from pets, public facilities, or environmental sources. The microscopic data thus support targeted treatment and education focused on sexual or close‑contact transmission.

Treatment and Prevention

Eradicating Pubic Lice

Over-the-Counter Treatments

Over‑the‑counter products remain the first line of defense against crab lice infestations. Two active ingredients dominate the market: permethrin 1 % cream rinse and pyrethrin‑based shampoos. Both are applied to the affected area, left for the recommended time (usually 10 minutes), then rinsed off. A second application 7–10 days later eliminates newly hatched nymphs.

- Permethrin 1 %: kills adult lice and nymphs; safe for most adults and children over two months; may cause mild skin irritation.

- Pyrethrin combinations (often with piperonyl‑butoxide): effective against live insects; can provoke allergic reactions in sensitive individuals; not recommended for infants under two months.

- Dimethicone lotion: silicone‑based, suffocates lice; non‑neurotoxic; suitable for pregnant or nursing persons; requires thorough coverage and repeat treatment after 7 days.

Adjunct measures increase success. Wash all clothing, bedding, and towels in hot water (≥ 60 °C) and dry on high heat. Items that cannot be laundered should be sealed in a plastic bag for at least 72 hours, a period sufficient to kill lice and eggs. Vacuuming upholstered furniture removes stray insects. Avoid sexual contact or close skin‑to‑skin contact until treatment is complete and symptoms have resolved.

Potential adverse effects are limited to localized itching, redness, or temporary burning sensation. Systemic toxicity is rare with OTC formulations when used as directed. Users with known hypersensitivity to pyrethrins or permethrin should select an alternative, such as dimethicone, or seek prescription therapy.

Correct application, adherence to repeat‑treatment timing, and comprehensive decontamination of personal items constitute the essential components of effective self‑managed therapy for pubic lice.

Prescription Medications

Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis) spread chiefly through intimate skin‑to‑skin contact, shared clothing, and bedding. After exposure, prescription‑only drugs are required for definitive eradication when over‑the‑counter options fail or resistance is suspected.

- Ivermectin, oral, 200 µg/kg single dose; repeat after 7 days if live lice remain.

- Permethrin 5 % cream, applied to affected area for 10 minutes, then washed off; repeat in 7 days.

- Malathion 0.5 % lotion, applied to dry skin, left for 8–12 hours before removal; a second application after 7 days may be needed.

Ivermectin disrupts glutamate‑gated chloride channels, causing paralysis and death of the parasite. Permethrin interferes with neuronal sodium channels, leading to loss of nerve function. Malathion inhibits cholinesterase, resulting in accumulation of acetylcholine and fatal overstimulation of the nervous system.

Resistance to topical agents has been documented in several regions, prompting clinicians to prefer oral ivermectin or combination therapy. Prescription strength ensures appropriate concentration, reduced exposure time, and compliance monitoring.

Patients must complete the full treatment course, avoid re‑exposure, and wash all clothing and linens at temperatures ≥ 50 °C. Follow‑up examination after two weeks confirms clearance; persistent infestation warrants alternative prescription regimens.

Home Remedies (Effectiveness)

Pubic lice infestations arise from close physical contact, especially sexual activity, and from sharing contaminated fabrics such as towels or bedding. Once introduced, the insects cling to coarse body hair and feed on blood, causing itching and irritation. Eliminating the parasites promptly reduces transmission risk and alleviates symptoms.

Home treatments are frequently suggested, yet scientific evidence supporting their efficacy is limited. The following remedies have been evaluated in clinical observations and laboratory studies:

- Vinegar (acetic acid) rinses – mild acidity may loosen lice from hair shafts, but does not reliably kill eggs; effectiveness considered low.

- Tea tree oil (Melaleuca alternifolia) – topical application shows some insecticidal activity in vitro; limited human data, moderate effectiveness when combined with a carrier oil.

- Neem oil (Azadirachta indica) – demonstrated ovicidal properties in laboratory settings; real‑world results vary, moderate effectiveness reported.

- Petroleum jelly (Vaseline) – suffocates adult lice when applied thickly for several hours; studies indicate partial success, low to moderate effectiveness, especially against nymphs.

- Hot water washing – laundering clothing, bedding, and towels at ≥60 °C for 30 minutes destroys lice and eggs; high effectiveness, recommended as adjunct to any treatment.

- Hair trimming – reducing hair length limits habitat; does not eradicate lice but can facilitate removal; low effectiveness as sole measure.

Prescription pediculicides (e.g., permethrin 1 % cream rinse, pyrethrins with piperonyl‑butoxide) remain the most reliable option, achieving cure rates above 90 % when applied correctly. Home remedies may serve as supplementary measures but should not replace approved topical agents. Continuous cleaning of personal items and avoidance of shared textiles are essential to prevent re‑infestation.

Preventing Reinfestation

Personal Hygiene

Pubic lice, scientifically known as Pthirus pubis, are ectoparasites that live on coarse body hair. Their primary source is direct human-to-human contact, most often sexual activity, but they can also spread through prolonged skin‑to‑skin interaction and sharing of contaminated personal items such as towels, underwear, or bedding.

Personal hygiene does not eradicate lice, yet it reduces the risk of infestation. Regular washing of the genital area with soap and water removes debris that may attract parasites, while frequent laundering of clothing and linens at temperatures above 60 °C kills any attached insects or eggs.

Preventive measures include:

- Avoiding the exchange of personal garments, especially undergarments and towels.

- Using separate laundry for intimate apparel and washing it in hot water.

- Inspecting new sexual partners for signs of infestation before intimate contact.

- Maintaining clean, dry environments for body hair to discourage lice survival.

If an infestation occurs, prompt treatment with approved topical insecticides, combined with thorough cleaning of all potentially contaminated items, is essential to eliminate the parasites and prevent re‑colonization.

Partner Notification and Treatment

Pubic lice are transmitted through close skin‑to‑skin contact, most commonly during sexual activity. When an individual is diagnosed, immediate notification of recent sexual partners is essential to prevent reinfestation and halt further spread.

The notifying individual should:

- Identify all partners with whom intimate contact occurred within the previous four weeks.

- Communicate the diagnosis promptly, using clear language that the infestation is treatable.

- Encourage each partner to seek medical evaluation without delay.

Treatment for all affected persons must be simultaneous. Recommended regimens include:

- Application of a 1% permethrin cream or lotion to the affected area, left for ten minutes before washing off; repeat after seven days.

- Use of a 0.5% malathion lotion applied similarly, for cases resistant to permethrin.

- Oral ivermectin (200 µg/kg) as a single dose, with a repeat dose after seven days for severe or refractory cases.

Follow‑up examination 1–2 weeks after therapy confirms eradication. If live lice or viable eggs persist, repeat the chosen regimen. All partners should be retested after completion of treatment to ensure clearance.