Anatomy of a Tick

External Structures

Head (Capitulum)

The anterior region of a tick, termed the capitulum, appears as a compact, three‑dimensional structure when examined at 100–400 × magnification. The cuticle is thin, semi‑transparent, allowing internal sclerotized elements to be distinguished against a lightly pigmented background.

- « Chelicerae » – paired, curved, knife‑like appendages situated laterally; each consists of a basal segment and a distal fang that can be seen as a darkened tip.

- « Hypostome » – central, barbed feeding tube projecting ventrally; its surface shows a series of denticles arranged in regular rows, visible as fine, parallel lines.

- « Palps » – short, segmented sensory organs flanking the hypostome; under the microscope they appear as elongated, slightly lighter rods with distinct articulations.

- « Basis capituli » – basal sclerite that anchors the chelicerae and palps; presented as a robust, roughly triangular plate with a smooth margin.

The capitulum measures approximately 0.2–0.5 mm in length, depending on species and developmental stage. In larval ticks the structures are proportionally smaller and less sclerotized, while adult specimens exhibit a thicker cuticle and more pronounced dentition on the hypostome. The overall morphology provides a clear identification marker for taxonomic and epidemiological investigations.

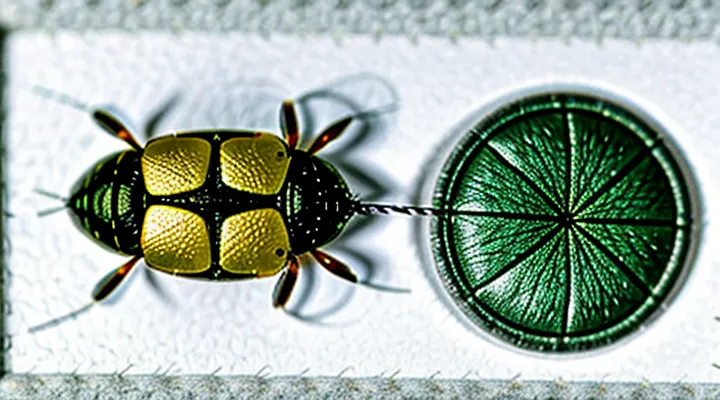

Body (Idiosoma)

The idiosoma, the main body segment of a tick, appears as an oval to slightly elongated capsule when examined under a light microscope. Dimensions range from 0.5 mm in larvae to several millimetres in adult females, with the dorsal surface covered by a hardened cuticle.

Key morphological elements visible on the idiosoma include:

- Dorsal shield (scutum) in males, a rigid plate extending over most of the dorsal surface; in females, a smaller scutum leaves the posterior region exposed.

- Festoons, a series of rectangular plates along the posterior margin, each delineated by a distinct suture.

- Setal bases and sensilla, appearing as small, dark puncta embedded in the cuticle.

- Spiracular plates located laterally, each housing a pair of openings for respiration.

- Anal groove and anal plate situated ventrally, distinguishable by a shallow depression and a hardened rim.

Staining with hematoxylin‑eosin or Giemsa highlights internal organs such as the midgut, salivary glands, and reproductive structures, allowing differentiation of tissue layers beneath the cuticle. Scanning electron microscopy resolves surface topography, revealing micro‑ornamentation of the scutum, the arrangement of setae, and the fine structure of the spiracular openings. The combined use of light and electron microscopy provides a comprehensive view of the idiosoma’s architecture, essential for accurate species identification and physiological studies.

Legs

Ticks possess eight legs, a defining characteristic of arachnids that becomes evident under magnification. Each leg consists of six distinct segments: coxa, trochanter, femur, patella, tibia, and tarsus. The coxa attaches directly to the body’s dorsal shield, while the distal tarsus ends in a small claw used for anchoring to host tissue.

The legs display a pale, semi‑transparent cuticle that reveals underlying muscle fibers and hemolymph channels. Microscopic observation often shows fine setae (sensory hairs) distributed along the dorsal surface of each segment. These setae vary in length, with longer filaments on the femur and tibia, providing tactile feedback during host detection.

Key morphological details observable at high magnification include:

- Segmental articulation: Clear joints between each segment, allowing precise movement.

- Sclerotized tips: Hardened claws at the tarsal ends, contrasting with the softer cuticle of the proximal segments.

- Sensory structures: Microscopic pores and chemoreceptive pits near the base of the setae, facilitating detection of carbon dioxide and heat.

The arrangement of legs follows a symmetrical pattern: four pairs positioned laterally on the ventral side of the idiosoma. In engorged specimens, the legs appear contracted, with the cuticle stretched over a larger body volume, yet the segmentation remains discernible. This consistent leg architecture aids taxonomic identification and provides insight into the tick’s locomotion and host‑attachment mechanisms.

Microscopic Features of a Tick

Mouthparts

Hypostome

The hypostome is the ventral feeding organ situated at the anterior end of a tick. Under light microscopy it appears as a compact, sclerotized structure protruding from the mouthparts. Its surface is covered with numerous backward‑pointing denticles that interlock with host tissue, providing a firm attachment during blood ingestion.

Microscopic characteristics include:

- Dense arrangement of cuticular spines, each tapering to a sharp tip.

- Central canal that houses the salivary duct and channels blood flow.

- Thickened basal region that merges with the chelicerae and pedipalps.

- Uniform pigmentation, often darker than surrounding cuticle, enhancing contrast in stained preparations.

When stained with hematoxylin‑eosin, the hypostome exhibits a deep blue‑purple hue in the cuticular matrix and a lighter eosinophilic staining of the internal canal. Scanning electron microscopy reveals the three‑dimensional architecture of the denticles, showing their precise angulation and spacing that facilitate secure anchorage.

The hypostome’s morphology varies among tick families; ixodid species typically possess a more robust, heavily denticulated hypostome compared with argasid counterparts, reflecting differences in feeding duration and host interaction.

Chelicerae

The chelicerae of a tick are the pair of short, robust mouthparts located ventrally near the anterior margin of the idiosoma. Under light microscopy they appear as dark, sclerotized structures about 0.1–0.2 mm in length, each consisting of a basal basal segment (the basal cheliceral segment) and a distal fang‑like portion that terminates in a sharp tip. The basal segment is typically broader and bears a series of fine grooves that accommodate muscles, while the distal portion is tapered and may exhibit a slight curvature that assists in piercing host skin.

When a tick is examined at 400–1000× magnification, the following features become evident:

- Cuticular ridges on the outer surface of each chelicera, providing structural reinforcement.

- Microscopic setae lining the inner edges, contributing to sensory perception during feeding.

- A visible articulation joint between the basal and distal segments, allowing limited movement essential for the insertion of the feeding tube.

The chelicerae function in conjunction with the hypostome to anchor the tick to its host, enabling the transfer of saliva and the ingestion of blood. Their morphology, observable under a microscope, distinguishes tick species and aids in taxonomic identification.

Pedipalps

Microscopic examination of ticks reveals a complex arrangement of appendages; the anterior pair known as «pedipalps» is readily observable at moderate magnification.

«Pedipalps» consist of a basal segment (the coxal region) attached to the gnathosoma, followed by a short, stout palpal segment ending in a flexible claw. The surface bears dense setae and sensilla that appear as fine, hair‑like projections under bright‑field illumination.

Positionally, the pedipalps flank the chelicerae, projecting forward from the ventral side of the idiosoma. Their orientation permits close contact with the host’s skin during attachment.

Key observable characteristics include:

- Length typically 0.15–0.30 mm, proportionate to the tick’s overall size.

- Segmentation visible as a slight constriction between basal and distal portions.

- Presence of tactile setae, appearing as bright, linear structures when stained with iodine.

- Flexibility of the terminal claw, observable as a slight curvature in live specimens.

Under higher magnification (400–600×), the cuticular layers of the pedipalps display a layered texture, with the outer epicuticle appearing smooth and the underlying exocuticle showing a reticulate pattern. Fluorescent staining highlights the sensory organs, enhancing contrast between the pedipalps and adjacent structures.

Overall, the pedipalps serve as primary sensory and grasping organs, their morphology and surface features providing essential clues for species identification and for understanding the attachment mechanism of ticks.

Integument (Skin)

Setae

The microscopic examination of ticks reveals a dense covering of hair‑like structures known as «setae». These cuticular bristles protrude from the dorsal and ventral surfaces, providing tactile and sensory functions. Under light microscopy, setae appear as slender, elongated filaments measuring 10–30 µm in length, often slightly curved and terminating in a tapered tip.

Key morphological features observable in setae include:

- Uniform thickness along the shaft, with occasional basal thickening.

- Surface ornamentation such as fine ridges or pores, visible at higher magnification.

- Arrangement in rows or clusters that correspond to specific body regions, aiding in species identification.

Scanning electron microscopy further details the micro‑architecture, showing cuticular layers, occasional spines, and the attachment points to the integument. The presence, density, and pattern of «setae» contribute to taxonomic differentiation and provide insight into the tick’s interaction with its environment.

Pits and Pores

Microscopic examination of ticks reveals a patterned cuticular surface where depressions and openings play distinct roles in physiology and pathogen transmission.

The depressions, commonly referred to as pits, appear as shallow, regularly spaced cavities measuring 5–15 µm in diameter. They are most abundant on the dorsal scutum and ventral plates, providing anchorage points for sensory setae and facilitating expansion of the cuticle during engorgement. The walls of each pit are composed of chitinous laminae that impart structural rigidity while allowing limited flexion.

Openings known as pores punctuate the tick’s integument. Two principal categories exist:

- «respiratory pores» – minute apertures (~1 µm) located along the spiracular plates, connecting the tracheal system to the external environment; they are encircled by sclerotized rims that prevent desiccation.

- «glandular pores» – slightly larger channels (2–4 µm) distributed across the salivary glands and midgut epithelium, serving as conduits for secretion of enzymes and for uptake of host blood components.

The spatial arrangement of pits and pores creates a mosaic that enhances cuticular flexibility, protects internal tissues, and supports the tick’s capacity to acquire and transmit pathogens.

Sensory Organs

Haller's Organ

Haller’s organ is the most distinctive sensory structure observed when a tick is examined microscopically. Positioned on the dorsal surface of the first pair of legs, the organ occupies a shallow pit surrounded by a cuticular rim. Under bright‑field or phase‑contrast illumination, the pit appears as a shallow depression approximately 120 µm long and 80 µm wide, with a clearly defined border of sclerotized cuticle.

The organ consists of two functional regions. The anterior capsule houses a cluster of chemosensory sensilla, each resembling a short, tapering hair with a porous wall. The posterior capsule contains mechanosensory setae, stout and rigid, projecting outward from a membranous base. Both regions are separated by a thin cuticular wall that is visible as a faint line across the pit.

Key microscopic characteristics:

- Deep, oval pit with cuticular rim

- Anterior capsule: numerous peg‑like sensilla, each ~5 µm in length, with a porous surface

- Posterior capsule: several thick setae, each ~10 µm long, terminating in blunt tips

- Intervening cuticular wall: translucent, ~2 µm thick

- Surrounding epidermal cells: densely packed, nuclei visible as small, dark circles

The precise arrangement of sensilla and setae provides a reliable diagnostic feature for tick species identification. When stained with a chitin‑binding dye, the cuticular structures acquire a bright orange hue, enhancing contrast and facilitating detailed morphological analysis.

Eyes (if present)

Ticks possess simple visual organs called ocelli, present in many, but not all, species. Each ocellus consists of a lens and a small number of photoreceptor cells, arranged in a shallow pit on the dorsal surface of the idiosoma. Under a light microscope at 100–200 × magnification, the lens appears as a translucent, convex structure measuring 30–50 µm in diameter, surrounded by a ring of pigmented cuticle that creates a distinct contrast against the surrounding integument.

Microscopic observation reveals additional details:

- Lens surface: smooth, slightly refractive, often appearing brighter than adjacent tissue when illuminated from above.

- Pigmented rim: dark brown to black, delineating the ocellar border and absorbing stray light.

- Photoreceptor cluster: dense arrangement of short, columnar cells beneath the lens, visible as a faintly stained region in histological sections.

- Position: typically located on the anterior dorsal shield (scutum) in adult females and males, absent or reduced in larval and nymphal stages of some species.

Species lacking eyes exhibit a uniform dorsal cuticle without the pigmented rim or lens structures. In those cases, the absence of ocelli is confirmed by the homogeneous appearance of the scutum and the lack of any refractive element under comparable magnification.

Comparison with Other Arthropods

Distinguishing Features

Under high magnification, a tick displays a set of morphological characteristics that differentiate it from other arthropods. These traits are essential for accurate identification and for distinguishing between species, life stages, and engorgement levels.

• Scutum – a rigid dorsal plate covering the anterior portion of the idiosoma; its shape, size, and ornamentation vary among species.

• Capitulum – the anterior mouth apparatus comprising the chelicerae, hypostome, and palps; the hypostome’s barbs indicate a blood‑feeding habit.

• Legs – eight jointed appendages, each ending in a claw; the presence of festoons or sensory pits on the legs aids in species discrimination.

• Alloscutum – the soft, expandable posterior region that enlarges markedly after a blood meal; its texture and coloration provide clues to engorgement status.

• Genital aperture – a ventral opening surrounded by a distinct sclerotized rim; its position relative to the anal groove is taxonomically relevant.

• Eyes – a pair of simple eyes located laterally on the scutum of many hard‑tick species; the presence or absence of eyes assists in family‑level classification.

The scutum’s surface may exhibit punctations, ridges, or a smooth finish, each pattern linked to specific genera. The capitulum’s hypostomal barbs are arranged in a characteristic pattern that distinguishes ixodid ticks from argasid counterparts. Leg morphology, including the number and arrangement of sensory pits, provides reliable markers for differentiating immature stages. The alloscutum’s elasticity permits dramatic size changes, observable as a clear expansion of the cuticle. The genital aperture’s sclerotized border offers a stable reference point for measuring morphological ratios used in taxonomic keys. Eye presence, combined with scutum characteristics, supports rapid family identification without molecular analysis.

Similarities

Microscopic examination of ticks reveals a set of structural features that remain consistent across species and developmental stages. These recurring characteristics enable reliable identification and comparative study.

- A dorsally positioned, shield‑like scutum covering the anterior portion of the idiosoma; in females the scutum is partial, allowing abdominal expansion during feeding.

- Four pairs of jointed legs emerging from the ventral margin, each bearing chelicerae and pedipalps near the mouthparts.

- A compact, oval‑shaped gnathosoma equipped with serrated chelicerae used for tissue penetration.

- Uniform cuticular layers exhibiting a pale, semi‑transparent appearance when observed with bright‑field illumination; staining with iodine or chlorazol black enhances surface patterning without altering overall morphology.

- Presence of a central dorsal groove, the “concave margin,” that separates the scutum from the surrounding cuticle in all examined specimens.

These similarities align ticks with other arachnids such as mites, reflecting shared evolutionary adaptations for ectoparasitism and host attachment. The consistency of these traits across life stages—larva, nymph, and adult—facilitates taxonomic classification and epidemiological monitoring.